Housing

The Mortgage Wall: In New Jersey, lenders deny home loans to Latinos more often than to white applicants

Table of contents

In July 2021, Jusleine Daniel, her husband and their 9-year-old daughter entered a branch of Investors Bank in Somerset, New Jersey, brimming with excitement. After years of hard work and setting money aside, the Latino family was ready to apply for a mortgage to buy a home.

Daniel felt more prepared than the average first-time homebuyer. Before approaching the bank for a loan, she’d made sure her credit was in good standing and taken a real estate licensing course to better understand the mortgage process. She’d also opened an account with Investors Bank, where she had more than $200,000 in savings from her private psychotherapy practice. The funds were meant to cover the down payment on a house.

When the loan officer at the bank asked for the family’s zip code, however, Daniel began to worry. In her real estate course, she’d learned about redlining—banks’ historic practice of denying loans to communities of color and excluding Black and Latino homebuyers from certain neighborhoods. Armed with this knowledge, the officer’s mention of zip codes set off alarm bells in her mind.

“If it had been any other person, maybe that question would have meant nothing,” said Daniel, a licensed clinical social worker, business owner and artist who identifies as Afro-Latina.

Jusleine Daniel, her daughter Milena and her husband Martin Calvino. (Photo courtesy of Jusleine Daniel)

The rest of the meeting went badly, Daniel said. The loan officer objected to a change in the family’s earnings, noting that the income generated by Daniel’s business had declined the previous year. He barely glanced at the other paperwork Daniel had assembled and didn’t bother checking her credit history or account balance, according to a complaint she filed with the state attorney general’s office. At the end of the meeting, the officer did not provide the family with a mortgage application.

“We were rejected even before applying,” Daniel said. “He saw a Black woman with an accent and a Latino guy with an accent and … we never got past that.”

Investors Bank was acquired by Rhode Island-based Citizens Financial Group in April 2022. A Citizens spokesperson said the company couldn’t comment on Daniel’s case because it occurred before the acquisition. They also stressed their “commitment to creating an inclusive culture” for their “expanding customer base.”

Daniel was denied an opportunity to apply for a mortgage in New Jersey. Other Latino residents who succeed in applying still face an uneven road to homeownership.

An investigation by Futuro Investigates found that between 2018 and 2022, financial institutions in New Jersey rejected Latino mortgage applicants at higher rates than their white counterparts. Latinos who did get mortgages, meanwhile, paid higher interest rates than white borrowers on comparable home loans.

U.S. Census worker in New Jersey. (AP Photo/Mel Evans)

To identify potential disparities in lending outcomes, we analyzed hundreds of thousands of mortgage applications filed in New Jersey from 2018 to 2022. We focused on conventional mortgages—loans offered by private companies—rather than loans backed by the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which tend to have looser qualification standards but higher closing costs.

This data is made publicly available under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA), a 1975 statute requiring financial institutions to collect and share information on lending activity with the federal government.

After filtering our dataset to focus only on the clearest application outcomes, we found that more than 11% of conventional loan applications submitted by Latinos resulted in denials—higher than the overall denial rate of 8% and roughly double the rate for white borrowers. A substantial disparity persisted even after we considered key variables, including debt, loan amounts and income.

The difference in denial rates tells a straightforward story: Latinos in New Jersey are more likely to be denied conventional mortgages than white residents.

Data analysis by Jeremy Singer-Vine and data visualization by Fernando Becerra.

Racial and ethnic disparities in mortgage lending are well-documented. In recent years, a growing number of studies have found that Black and Latino mortgage applicants are denied at higher rates than similarly qualified white borrowers. Some analyses even suggest that lenders reject borrowers of color more often than white applicants with riskier financial profiles.

These disparities are the legacy of discriminatory policies that shaped the U.S. lending system and endured well into the 20th century, experts told Futuro Investigates. The federal government instituted and encouraged redlining before banning it under the 1968 Fair Housing Act. Since then, illegal practices from lenders have continued shutting Americans of color out of homeownership.

“Our modern housing finance system was really built on a bedrock of systemic discrimination and racism,” said Amalie Zinn, a researcher specializing in mortgage lending at the Urban Institute, a nonpartisan think tank based in Washington, D.C. “We often think about how these policies excluded Black people, and that’s certainly true, but redlining also explicitly excluded Latino people.”

A Persistent Disparity

Daniel always dreamed of buying a house, but her quest for homeownership began in earnest when her daughter Milena was born in 2012. After renting a series of apartments in the Tri-State area, she and her husband signed a lease in Highland Park, a quiet, leafy borough in Middlesex County, New Jersey.

“I’ve moved in my whole life at least 50 times,” said Daniel, who was born in Los Angeles but grew up in Argentina. “So for me, when I had my daughter, there was no question … I was going to give her that stability.”

Highland Park became a home for Daniel and especially for Milena, who grew attached to its shops and playgrounds and formed friendships with other local kids. Its spacious apartments also provided a workspace for Daniel’s husband, Martin Calvino, a Uruguay-born multimedia artist and scientist. When the family was ready to buy a house, Daniel was eager for Milena to spend the rest of her childhood in the borough.

Milena, Daniel’s daughter, in Highland Park, New Jersey. (Photo courtesy of Jusleine Daniel)

“She calls Highland Park her little town,” said Daniel, who attended college at nearby Rutgers University and returned to the area to raise Milena. “There is that sense of safety … that allows us to really feel comfortable with the neighborhood.”

To Daniel, leaving Investors Bank without a mortgage application was a message from the lending industry that her family didn’t belong in Highland Park, a majority-white area where only 11% of residents are Latino. It was also a reminder of the limited opportunities for social mobility afforded to people of color.

“I’ve been discriminated [against] all my life, so this wasn’t anything new,” she said. “If somebody doesn’t want you to be part of the American Dream … [they] will put a stumbling block in your way.”

The mortgage process contains stumbling blocks for many prospective homebuyers. When deciding whether to approve a home loan, financial institutions consider numerous factors, including an applicant’s debt-to-income ratio (their monthly debt weighed against their monthly income), credit history and the presence of any co-applicants.

These factors can put Latino mortgage applicants at a disadvantage, experts told Futuro Investigates. Many come from households supported by multiple earners or have non-traditional incomes—including cash earnings—not properly captured by underwriting systems. Others may struggle to build credit due to limited access to banking services or misgivings about taking on debt.

“The current loan underwriting criteria poses some really unique challenges for Latino borrowers because they really weren’t considered in its design,” Zinn, the researcher from the Urban Institute, explained. “If you come from a country where transactions are predominantly done in cash … you just might not be aware of the importance of debt to accrue credit in the U.S.”

To better gauge the impact of ethnicity on mortgage outcomes, Futuro Investigates’ analysis adjusted for differences in key variables that lenders consider when reviewing home loan applications. Among these variables were income, debt-to-income ratios, loan amounts and the presence of a co-applicant. This allowed us to compare application outcomes for borrowers who looked similar on paper except for their ethnicity.

Making these adjustments reduced but did not eliminate the gap in denial rates between white and Latino New Jerseyans. Even after considering complex factors like debt-to-income ratio and loan amount, Latino mortgage applicants faced higher odds of rejection than white borrowers.

Our adjusted analysis accounted for many of the factors that could explain differences in lending outcomes among similar applicants, independent experts confirmed.

“You’re doing the best you can given the data,” said José Loya, an assistant professor of urban planning at UCLA who’s researched lending patterns and reviewed Futuro Investigates’ analysis. “The variables that you’re using … live up to the standards that we normally see housing scholars use when measuring housing disparities in the U.S.”

Likewise, lending industry representatives who reviewed our methodology stressed that while it had limitations, there were no errors in our process or findings.

The analysis “seems to be careful and as complete as the HMDA data allows,” Falen Taylor, director of public affairs at the Mortgage Bankers Association, wrote in an emailed statement to Futuro Investigates. “That said … these types of analyses are just the first step into any investigation regarding lending disparities, as there is not sufficient data to make a determination on fair lending.”

Industry representatives have criticized past analyses of mortgage outcomes on similar grounds, saying they don’t fully account for lenders’ underwriting standards. Differences in denial rates, they’ve argued, can be explained by factors outside of race or ethnicity, including applicants’ credit scores.

“An individual’s credit history can help explain why seemingly comparable applicants may not always end up with the same lending outcome,” the American Banking Association wrote in response to a 2022 WBUR analysis of mortgage originations in Boston. “Any meaningful review of mortgage lending practices for possible discrimination … must also consider individual factors such as a borrower’s credit score.”

Data analysis by Jeremy Singer-Vine and data visualization by Fernando Becerra.

It wasn’t possible to incorporate credit scores into our analysis because that information isn’t included in publicly accessible mortgage data. We were, however, able to filter our dataset to exclude all mortgage applications that lenders said were rejected for credit-related reasons. If credit history plays an outsize role in mortgage outcomes—as lenders claim—removing these applications should theoretically have narrowed the gap in denial rates between Latino and white borrowers.

When we removed those credit-related denials, the disparities in outcomes—still considering variables such as debt-to-income ratio—barely changed, suggesting that factors beyond credit history contribute to differences in lending decisions. Prior research from the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau—which has access to credit score data—has also found that accounting for credit scores doesn’t erase disparities.

“The current mortgage application process … is not neutral on the basis of race and ethnicity,” Zinn said. “There is some discrimination that exists there, even if it’s unconscious.”

Fighting to Stay Put

Daniel refused to have her dreams of homeownership dashed by a single lender. Days after being denied a mortgage application at Investors Bank, she filed a Fair Housing complaint with the New Jersey Office of Attorney General’s Division on Civil Rights.

“The idea of doing the complaint is for them to be accountable and … change the protocol” for evaluating mortgage applicants, she said. “I want the [lender] to know that … they are not gonna get away with it.”

Daniel pursued the complaint for two years before the process became too taxing. Investors Bank attorneys overwhelmed her with repeated demands for records and other documents, she said, and state regulators dismissed her case when she could no longer keep up.

While Daniel focused on the complaint, her husband sought to contextualize his family’s experience by analyzing mortgage application outcomes in New Jersey. Calvino’s research persuaded him that certain lenders in the state were more likely to reject Latino borrowers than white applicants.

Martin Calvino, Daniel’s husband, is a multimedia artist and scientist. (Photo courtesy of Jusleine Daniel)

Calvino was right to be concerned about potential discrimination within New Jersey’s mortgage industry. In the past several years, multiple lenders have reached multi-million dollar settlements with government regulators after being accused of steering services away from local communities of color. These settlements shine a light on the policies and practices that have fueled lasting inequities in the Garden State, experts told Futuro Investigates.

“In New Jersey, we often do think of ourselves as one of the most progressive states in the nation,” said Laura Sullivan, the director of the Economic Justice Program at the New Jersey Institute for Social Justice, a local research and advocacy group. “But when you look a little closer, you find that we have some of the highest racial disparities in the country. And that includes one of the largest racial wealth gaps … [and] substantial disparities in homeownership.”

In addition to uncovering disparities at a statewide level, Futuro Investigates tried to determine whether differences in lending outcomes varied among New Jersey counties.

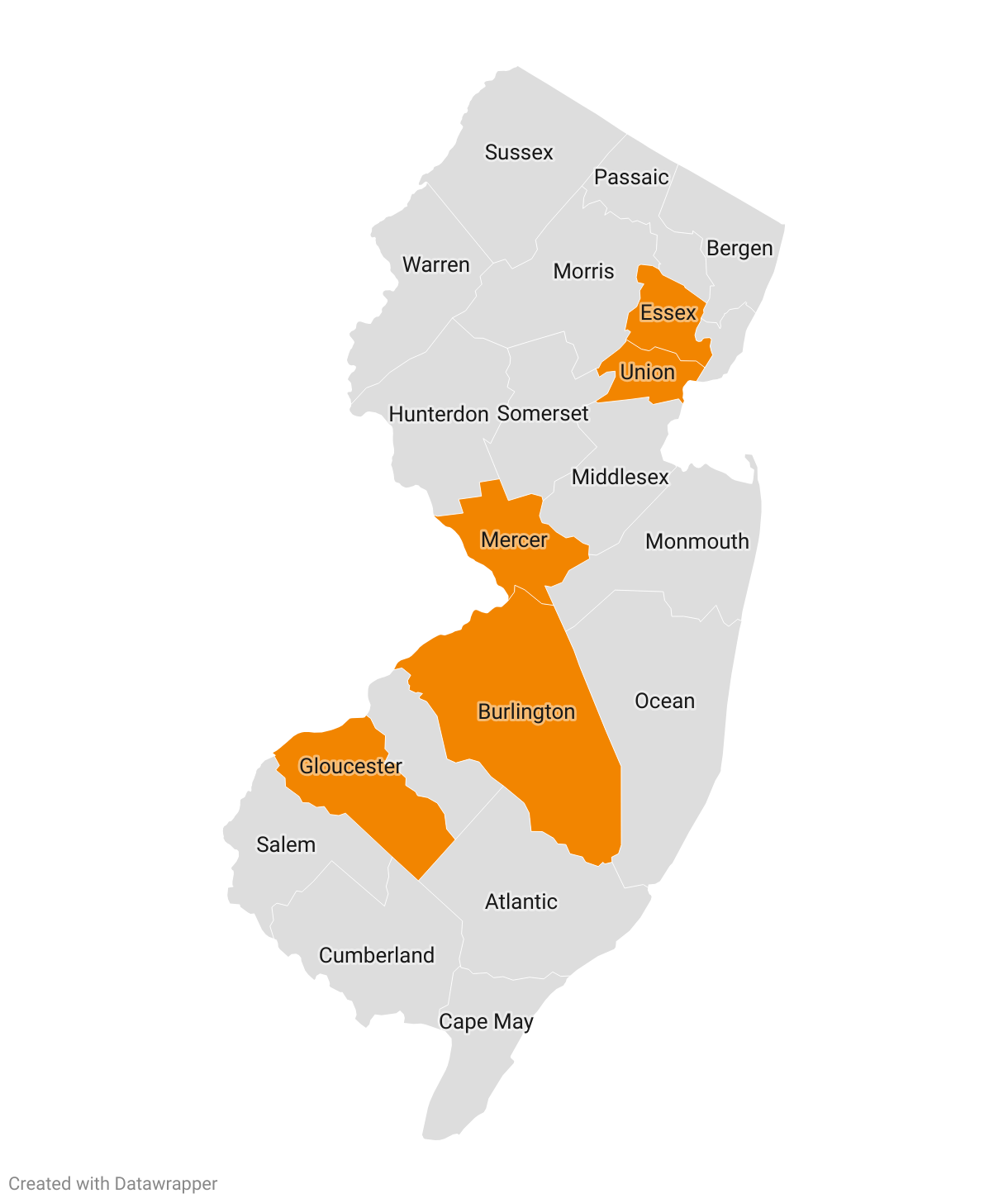

We found that Latino mortgage applicants in all 21 counties were rejected at higher rates than white residents. In five counties—Essex, Mercer, Gloucester, Burlington and Union—the difference amounted to more than six percentage points. Gloucester and Burlington counties showed the largest disparities after we adjusted for key application factors, including debt-to-income ratio.

In these five New Jersey counties, the difference in denial rates between Latino and white mortgage applicants amounted to more than six percentage points. (Nour Saudi for Futuro Media)

In Middlesex County—where Daniel and Calvino hoped to buy a home—lending disparities weren’t as stark. Still, according to our analysis, Latino mortgage applicants fared worse than white borrowers: 11% of their applications were rejected by lenders, compared with less than 7% of those submitted by white residents.

Data analysis by Jeremy Singer-Vine and data visualization by Fernando Becerra.

Besides sparking a complaint and a data analysis, being prevented from applying for a mortgage was a creative inspiration for Daniel and Calvino. Over the following months, they collected wooden doors discarded at construction sites, adorning them with drawings and findings from Calvino’s research on mortgage lending outcomes. Their final art installation, featuring a total of eight doors, was exhibited at Seton Hall University in 2022.

“The concept of a door is very embedded in our culture as a symbol of opportunity,” Calvino explained to Futuro Investigates at the exhibition. “It occurred to me that using doors … was a good way to convey the results of my data science project.”

Martin Calvino’s art exhibition at Seton Hall University. (Nancy Trujillo for Futuro Media)

Calvino’s data analysis—separate from Futuro’s own investigation—also helped the family research other lenders in the area. In November 2021, United Wholesale Mortgage, a national company with a footprint in New Jersey, approved Daniel and Calvino’s application for a 30-year home loan. A month later, the couple closed on a three-bedroom house in Highland Park.

Watching her daughter explore the property fulfilled a vision that Daniel had manifested years earlier.

“I always saw myself as a homeowner,” she said. “But my pleasure comes from seeing the joy that my daughter has saying that this is her home.”

Success, but at a Price

Nearly two years after Daniel and Calvino became homeowners, Futuro Investigates visited their house in Highland Park. The house looked stately and suburban from the outside, with a front porch, large windows and a well-kept hedge surrounding the front yard. Inside, art was everywhere: Large paintings by Daniel hung in the living room next to textiles from Calvino and drawings by Milena. One kitchen wall was covered with magnets—souvenirs from trips to countries like Spain, Norway and Bulgaria.

Filling every room with art and color was more than just an aesthetic preference for the family, Daniel explained. It was an expression of ownership.

“This is the first time that I find myself settled,” she said.

Daniel achieved her goal of remaining in Highland Park and getting a mortgage with terms she deemed favorable.

Jusleine Daniel in front of her house in Highland Park, New Jersey. (Peniley Ramírez for Futuro Media)

Other Latino families in New Jersey have been less fortunate. Futuro Investigates compared interest rates on loans offered to Latinos with rates offered to white borrowers. This required analyzing rate spread, a term that indicates how much higher or lower a borrower’s interest rate is than the average low-risk borrower for a comparable loan.

Our analysis showed Latinos were more likely to receive high or disfavorable rate spreads on mortgages than white borrowers. Using the same subset of loans as we did when assessing mortgage denials, we found Latinos had a median rate spread of 0.35—roughly double that of white borrowers. Adjusting for factors like debt-to-income ratio narrowed this disparity but didn’t eliminate it entirely.

Data analysis by Jeremy Singer-Vine and data visualization by Fernando Becerra.

Our findings were consistent with national research showing that when Black and Latino borrowers are approved for home loans, they tend to pay higher interest rates and steeper upfront fees than white borrowers with similar financial profiles. These additional costs prevent borrowers of color from reaping the full financial benefits of homeownership—widely considered the best approach to building wealth.

“If you’re paying a higher interest rate [on a mortgage], then your ability to realize wealth from your … home is diminished,” Zinn of the Urban Institute said.

Daniel credits being denied a mortgage application deepening her understanding of the lending system and its shortcomings. She hopes her story will inspire other Latinos in and outside New Jersey to see their dreams of homeownership through.

“At some point, your experiences need to make meaning for other people,” she said. “That’s how you create harmony that eventually can make changes.”