Border, Immigration

How U.S. policies contributed to a crisis in the Arizona Desert

Table of contents

As the death toll across the border continues to rise, volunteer organizations go out into the most dangerous areas to search for missing people. Futuro Investigates examine why volunteers, lacking financial resources, continue to take on this dangerous work while Border Patrol’s multi-billion budget continues to increase.

TUCSON, Arizona. Among the boundless hills and valleys of the Sonoran desert adorned with soaring saguaro cacti, prismatic prickly pears and curled chollas, thousands of people attempting to migrate into the United States from Mexico have lost their lives trying to cross this stretch of the Arizona border.

More than 8,000 deaths have been recorded on the southwest border since 1998, according to the U.S. Border Patrol. Out of the agency’s nine patrol sectors on the southern border, the Tucson sector, which covers most of Arizona, has had the most cumulative deaths. Four of every 10 recorded deaths on the southern border have occurred here. However, experts say the federal government’s death estimates are unreliable.

“The true number of migrant deaths that are occurring in a given year, we just don’t know,” said Daniel Martínez, co-director of the Binational Migration Institute at the University of Arizona.

The sheer size and difficulty of its terrain lead border crossers to die every year. The Sonoran Desert is over 100,000 square miles and stretches from northern Mexico and Baja California to southern Arizona as well as a small part of California. The punishing heat makes it the hottest desert in the United States, where temperatures can creep to nearly 120 degrees.

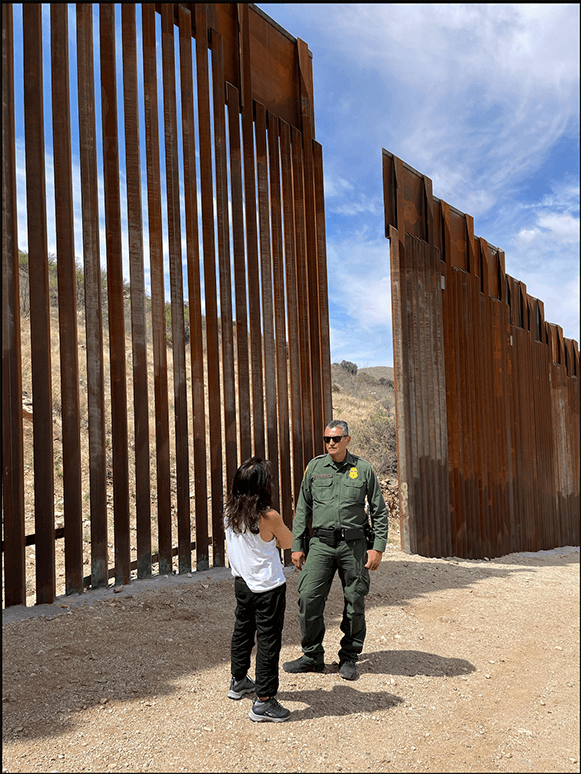

Experts say that this deadly crisis was created by the U.S. government’s own immigration policies and that these deaths don’t have to happen. A network of activists, volunteers, non-profit organizations and academics share a common mission of filling in where they believe the federal government has fallen short. They point to decades of policies that have pushed migrants into the most dangerous parts of the border to cross.

For years, self-funded search and rescue groups have been helping families find loved ones who have disappeared in the inhospitable terrain of the desert. While the Border Patrol has its own search and rescue arm, the agency also takes credit for rescues done by these volunteer groups.

*Among the nine U.S. Border Patrol sectors along the southwest border, the Tucson sector, which covers most of Arizona, has had the most cumulative deaths. From Fiscal Year 2002 to 2013, Tucson led with the most deaths per year. Since 2014, the Rio Grande Valley sector in Texas has surpassed Tucson with the most deaths per year. Data for this story were obtained by Futuro Investigates through publicly available documents as well as open records requests. Data visualization by Daniela Guazo, and Daniel Gómez Hernández of the Border Center for Journalists and Bloggers.

A Decades-Long Problem

Despite the harsh climate, for years a myriad of migrants have tried their luck to cross into the United States.

“In the past, maybe people would spend a few hours crossing the U.S.-Mexico border,” Martínez said. “Today, it’s not uncommon for people to spend several days out there.”

Martínez, a professor of sociology, has spent much of his career studying immigration, criminology, race, and ethnicity. In the past, those attempting to cross into the United States would use well-known, safer, routes going through large cities like San Diego or El Paso.

Then in 1994, the U.S. Border Patrol adopted a measure aimed to curb unauthorized immigration. Backed by President Bill Clinton, the strategy known as “Prevention Through Deterrence” increased funding and Border Patrol agents at common routes through which people would cross. They began setting up roadblocks, increased the number of patrols, and made it much more difficult for people to cross. Later came even more funding for a growing border wall. Today, Border Patrol’s funding is about five billion dollars.

Martínez and others who study migration say the increase in deaths are a direct consequence of policies like ‘Prevention Through Deterrence.” He said that there have always been deaths at the border, but not to the same scale or extent.”

He added that policymakers acknowledged in government documents that migrant deaths would likely happen.

“So not only were migrant deaths anticipated, but they were predicted,” he said.

*Nearly 3,000 deaths have been recorded by the U.S. Border Patrol in the Tucson Sector since fiscal year 1998. Tucson accounts for nearly 40% of all recorded deaths on the southwest border. Because of the vastness of the desert and the speed with which the remains can decompose and be scattered by prey, the true number of deaths in the desert is unknown. Data analysis and visualization by Daniela Guazo and Daniel Gómez Hernández of the Border Center for Journalists and Bloggers.

Death in the Desert

There are three options to the end of a journey for those crossing the border: a “successful” crossing where a person survives the desert to make it to their destination in the U.S., being detained and deported by the Border Patrol or dying.

Advocacy organizations such as Humane Borders and No More Deaths hope that making water available for people crossing the arid desert will help stop the number of deaths. While Humane Borders has worked with local government officials to be allowed to set up permanent water reservoirs that they fill up and inspect weekly, other groups hike into remote areas of the desert in order to leave jugs of water and first aid supplies in places where the most deaths have been reported.

One of the Border Patrol’s solutions to people dying in the desert is installing rescue beacons. The towering thirty-foot tall poles with a strobe light on top are meant to be seen from miles away by border crossers. At the base of the beacon is a box with a red button that people can press to receive help by the agency.

Border Patrol said the beacons are not an enforcement tool, but a humanitarian one. However, there’s no indication anywhere on the devices that they are associated with the federal law enforcement agency. There’s also no water, which could help a dehydrated person. And once an agent shows up, the person who activated the button is detained and ultimately deported.

About 160 beacons have been deployed along the southwest border. Border Patrol insists there are thousands of activations every year—though it’s unclear how many of those lead to rescues. Furthermore, according to the agency, those red buttons are not pressed as much as they used to be since many border crossers have cell phones.

Those with phones can call 911. By law, however, those calls must be re-routed to Border Patrol. That means people are asked to wait on hold while they run out of water, expend their energy or their cell phone dies.

Futuro Investigates obtained audio of 911 calls made by people who were lost and seeking rescue between June and September 2021. Deciding to publish these 911 calls led to a deep internal discussion among our team. The pushback centered around the potential for trauma for listeners, loved ones who may recognize the voice of the person—especially those who appear to not have been found. Online searches did not yield the necessary information to contact family members of the callers. In the end, our executive leadership made the decision to publish the calls for the public interest in an effort to provide firsthand accounts of the migrant experience in the desert.

During the calls, 911 dispatchers kept migrants pleading for help on hold. Some border crossers called multiple times. Some were eventually found by the Border Patrol. Others were not located, according to the Pima County Sheriff’s Office.

A report released by the advocacy group No More Deaths questions how much Border Patrol actually does when migrants call in distress. The report analyzed more than two thousand transferred calls between 2016 and 2018 made to the Pima County Sheriff’s Office. No More Deaths found that, for years, the majority of emergency calls were dropped once they were transferred to Border Patrol. It further evaluated requests made to the Derechos Humanos Missing Migrant Crisis Line. The community initiative, staffed by volunteers, assists families searching for loved ones. According to the report, nearly two-thirds of cases that volunteers referred to Border Patrol didn’t yield a search and rescue mission.

Though the Border Patrol pats itself on the back for its humanitarian work via social media and press releases, the data shows that people are kept waiting for help and, more often than not, left stranded in the desert.

*These calls have been edited. Data analysis and visualization by Daniela Guazo and Daniel Gómez Hernández of the Border Center for Journalists and Bloggers.

How to Count an Insurmountable Problem

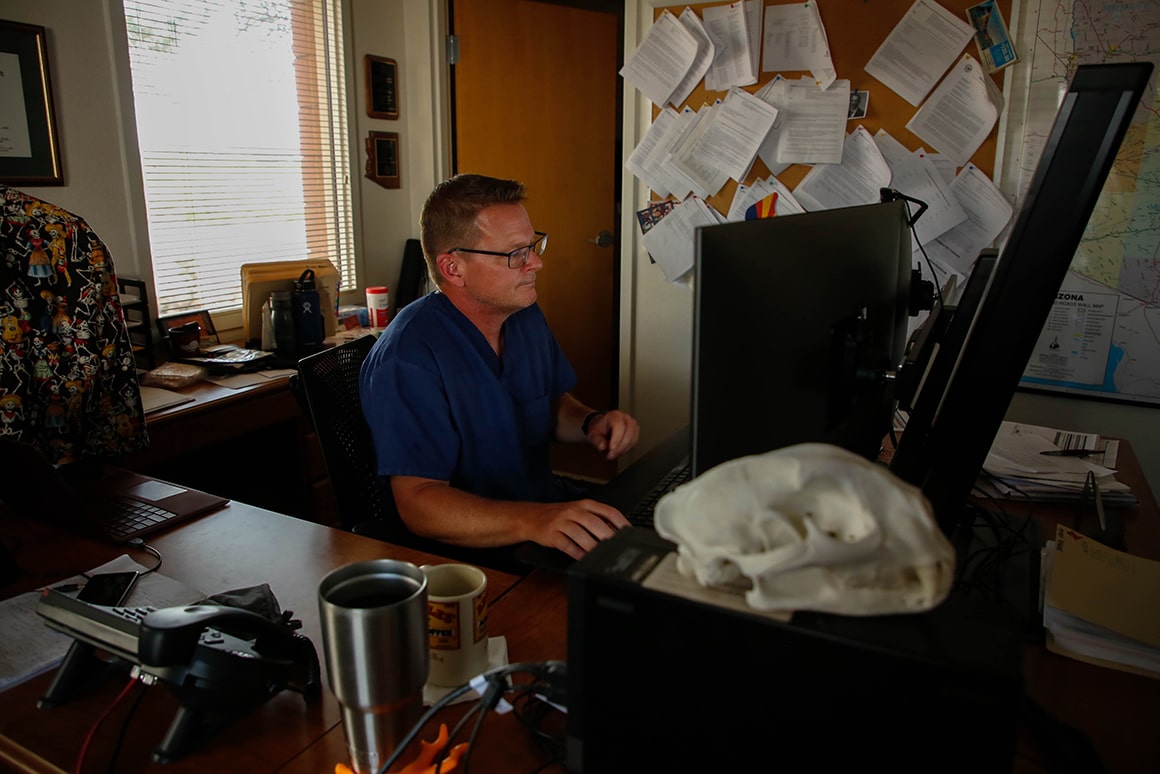

Because of the various local jurisdictions along the border, how the remains are treated largely depends on where they’re found. For many activists, the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner is the gold standard on how to process and record remains. In the last two decades, this office based in Tucson has handled more than 3,600 cases.

The office also has a partnership with the organization Humane Borders, which counts the number of deaths in the desert. Many experts say this map is more comprehensive than Border Patrol’s records.

Border Patrol has not collected, recorded or reported complete data to Congress about migrant deaths, according to a U.S. Government Accountability Office report released earlier this year. For example, Border Patrol’s fiscal year 2020 report to Congress did not contain complete data on migrant deaths.

*Border Patrol’s statistics on deaths differ from the one collected by Humane Borders, a nonprofit whose mission is to save people crossing the desert. Through a partnership with the Pima County Office of the Medical Examiner, the organization maintains a map of migrant deaths. Many experts say Border Patrol is not transparent in how it records death data. Data analysis and visualization by Daniela Guazo and Daniel Gómez Hernández of the Border Center for Journalists and Bloggers.

After working on border issues for many years Robin Reineke, an anthropologist at the University of Arizona, is conflicted about tallying the dead. “How many will it take before a large sector of the U.S. population cares that people are losing their lives and their bodies are decomposing in the desert.”

But she recognizes that having a historic record is a way of honoring and respecting the dead as well as their children and families.

“For them to understand that what happened to their parents wasn’t their fault, it wasn’t their family’s fault, it wasn’t their parents fault. It was a policy issue,” she said. “That’s why we count.”

Reineke founded the Colibrí Center for Human Rights. Until 2019, she was the center’s director. The organization helps identify people who have died on the border, and reunites their remains with loved ones. Often, Colibrí is the last resource for desperate relatives of those missing that haven’t gotten answers by the U.S. government.

Many families learn about Colibrí through social media and word-of-mouth. Mirza Monterroso, director of the missing migrant program at the center, tries to get basic information about missing loved ones during the hour-long intake process over the phone.

“Usually when they call they are in a lot of distress,” she said. “But it’s also a time to just hear the family and let them express themselves.”

Monterroso is used to dealing with grave topics. She previously worked as an archeologist digging up burial sites created by the Guatemalan genocide. However, learning about the beauty and brutality of the Arizona desert left her at odds.

“I was feeling guilty for having a plate of food or having a blanket to cover knowing that maybe just a few miles away there are people sleeping on the floor and dying [in the desert].”

For Perla Torres, the family network director at Colibrí, the fact that her job exists speaks to the lack of accountability when it comes to deaths in the desert. “It’s really unbelievable that no one else is picking up these families’ calls.”

“This isn’t a new issue,” Torres said about border deaths. “This isn’t something that has come all at once. It’s continuously happening.”

Reineke, the anthropologist, considers that not only are there laws that push people to death and disappearance but there are also policies to make it difficult to find information of those who have disappeared.

“They are blocked from various systems that are available to somebody like me,” she said. For example, Reineke said it’s also difficult or even impossible for families to file a police report of a missing loved one. Other times, according to advocates, families are required to travel to the state where the person disappeared to file a report. For Reineke, the fact that a small organization like Colibrí can make DNA matches is a phenomenon.

“The tide of erasure and disappearance of this population is so massive and powerful that it’s an absolute miracle that we’re able to find anyone,” she said.

A Chance for Closure

Along with assisting families navigate the red tape of getting their remains, Colibrí also creates spaces for families to organize and view their loss as an issue of human rights.

In 2018, Reineke led a group of anthropologists, activists and families to advocate in front of the Inter-American Commission of Human Rights. At the hearing, which focused on disappeared border crossers, families testified before agencies such as the FBI and Border Patrol.

The purpose of the event was to try to persuade federal agencies to cooperate with nonprofits such as Colibrí to streamline the process of identifying remains. That includes comparing genetic samples that groups such as Colibrí have collected to unidentified samples in the federal database CODIS, or the Combined DNA Index System.

“We still to this day haven’t been able to do that,” Reineke said, “but that hearing was a step in the right direction.”

Reineke was also grateful that families had the chance to show pictures and share stories of their loved ones in front of federal officials so they can “live with their conscience of what it means to prioritize their interpretation of policies over human life.”

“It’s a beautiful, sacred, and providing place,” Reineke said of the Sonoran desert. “It’s been an incomplete use of this landscape to try to use it as a killing tool.”

“There are ways to survive in this beautiful but difficult landscape, adds Reineke. “But unfortunately, mostly migrants are not given the privilege.”

Colibrí also organizes grieving and funeral rituals for families once DNA has been matched. Torres, the family network director, said these events provide a full circle moment. What shocks her most about this work is how grateful families are when a match is made.

“Families are thankful to even have an answer,” Torres added. “Even if that answer, unfortunately, has been death.”

As devastating as it is to get confirmation of the death of a loved one, a DNA match means closure.

“It’s the bare minimum that we can do to really help someone heal.”