Reporter’s Notebook

A weekend search mission in the Arizona Desert: A reporter’s notebook

Table of contents

Pulitzer-Prize winning senior producer and investigative reporter Julieta Martinelli spent two days in the desert while investigating the deaths of migrants in Arizona, along with a group of volunteers called The Blue Armadillos. In this reporter’s notebook, she reflects on her experience while reporting for Futuro Investigates & Latino USA’s newest investigation, “Death by Policy: Crisis In The Arizona Desert.”

Reporter's Notebook

On a warm early morning in September 2021, I joined my colleague and producer Jess Alvarenga and a group of volunteers on a search and rescue mission. We set out to walk more than twenty-six miles, hiking deep into the Sonoran desert in southern Arizona, in an area known as el camino del diablo, or the “Devil’s Highway.”

The men were part of the Blue Armadillos, one of a handful of all-volunteer search and rescue teams working along the southwest border. They often go where many won’t: into the furthest and most dangerous desert terrain. There, they search for people who’ve disappeared, attempting to migrate to the U.S.

Crossing the desert is a strenuous journey. People must walk more than a week in extreme temperatures, with few, if any, natural water sources. A factor that further exacerbates the risk of medical emergencies and death is the physical impossibility to carry enough water to adequately hydrate for such a grueling journey. Many of the activists we spoke with say that people don’t fully understand the severity of the journey. Many don’t survive.

Before our trip, Angel Martinez, one of the heads of the Blue Armadillos, warned us that the desert takes a tremendous toll on people’s bodies. A local humanitarian aid volunteer who preferred to remain anonymous and was instrumental in helping us plan for this trip, recommended we try to “train like you’re training for a marathon.”

He gave us a long list of instructions and items we should carry. It included electrolyte salt tablets, moisture-wicking socks, tall hiking boots a size bigger than we typically wear, to accommodate swollen feet and to protect our ankles from snake bites, and pliers. Later, I learned these are to remove the painful needles of the cholla cacti.

At four a.m. on September 17, 2021, we met the Blue Armadillos outside of a gas station in Ajo, Arizona. We headed south towards the Organ Pipe National Monument to begin our search.

Within the first few miles of our hike, I realized how unprepared we were. That day the temperature reached a scorching 110 degrees. But one of the volunteers explained that the heat radiating off the ground, and rocks we climbed through, made it feel ten degrees hotter.With our water reservoirs, supplies, and recording equipment, each of our bags weighed well over thirty pounds.

I began to sink under the weight of my backpack. It felt like wading through water.

Early on the hike, I injured my knee when the sand gave way beneath one of my boots into a hole about a foot deep. One of the Blue Armadillos explained that gophers create intricate tunnels systems underground. Because they often plug the entrances, avoiding them is a game of chance. Venomous snakes, spiders, and other animals use the tunnels to escape the heat, so, along with an injury, you run the risk of getting bit.

A few minutes after me, one of the volunteers also fell. The hole he stepped into almost reached his hip. I thought about how easy it is for a person to suddenly get hurt, and how one injury can slow down a whole crew. Jess and I were lucky to be with the Blue Armadillos, who adjusted their pace for us. But people crossing don’t have that luxury. Slowing down can mean risking apprehension by the Border Patrol, or running out of water and food before the journey is over. All I could think of was the immense fear an injured person must feel to get left behind.

As the day progressed, the heat of the sand burned through the soles of our hiking boots. Even with the right tools and all the prep beforehand, I can’t tell how many moments I felt convinced that my body would be unable to take another step. How badly I rationed my water, and yet the desert stretched forward.

The terrain was scorching, shadeless, and endless. There was no escaping from the heat.

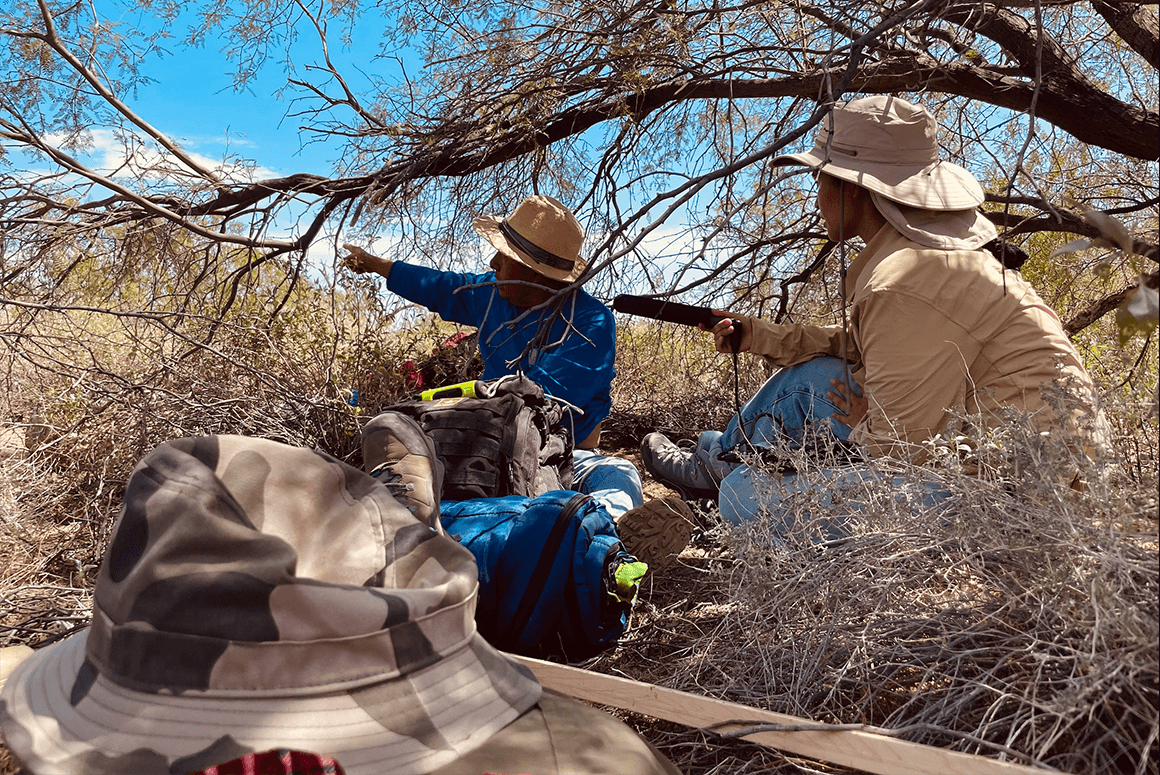

Hours into the hike, I felt like I’d lost control of all bodily functions. Gonzalo, one of the volunteers, tried to make conversation when he noticed I was starting to check out, but I had no energy to form words. I remember mumbling something and fixing my gaze on the mountain range ahead. They said that was our destination, but no matter how long we walked, it seemed we were no closer. A couple of times we found a few dry prickly bushes and lay for a few minutes under what tried to pass as shade. I remember a lizard running over my chest and thinking, “I’m just glad it’s not a snake.”

As we inched closer to the mountains, I was so tired I forgot all the warnings and walked right into a field of cholla. The needles of these cacti are attracted to body heat, “jump” off the cacti, and hook into your skin. The needles, which are shaped like the letter “J”, dug into my thighs, butt, and lower back.

I forgot the first rule of the cholla: “don’t touch.”

As I tried to dig them out, they clung to my hand, wrist, and arm. Ramon, one of the newer volunteers, pulled them off with pliers. It hurt. I bit my tongue, embarrassed I might cry (mostly from frustration). But there was no water for tears. He rubbed a numbing cream over the tiny wounds. We kept walking.

As the sun continued to beat down on us, the jokes and conversations stopped. The Blue Armadillos walked in silence—hot, cramping, tired. Exhausted, I thought how terrifying it must be to be here all alone. Every year, hundreds of human beings risk and suffer here while in pursuit of an uncertain future. How much strength and faith they possess to continue forth.

Without the Blue Armadillos, their advice, help, and encouragement, I felt certain that Jess and I would never make it through the weekend. How did people—children, families—survive a week in these conditions?

By sunset, we finally reached our destination. Here they split into teams of two, and spread out in a five-mile radius to search for a young man from Honduras named Johnny. Relatives of the missing man told the volunteers that Johnny was left behind by a coyote after he got injured, near the base of these mountains. Jess and I stayed back with two volunteers and set up camp as the sun began to set.

We removed our shoes and found our feet swollen, with big red blisters, and bleeding between our toes. One whole day of walking—that’s all we’d done, and our bodies were already breaking down. How does anyone make it out of here alive? Before coming, I didn’t realize how just one day could lead to this level of exhaustion.

But this isn’t like any other hike. The power of the desert was clear at the moment. And yet, people have to survive days and days of this, with fewer supplies, less preparation, the inability to stop and rest, and the fear of evading the routes covered by Border Patrol.

Later, as the rest of the group returned, we watched their slow gait at a distance. Their faces were weary and defeated. They hadn’t found the young man they were searching for. Rubén, one of the Blue Armadillos, ruptured the blisters under my feet with a warm blade. We passed around bandages to patch our sores and shared sips of water.

That night, we laid our sleeping bags in a circle. The volunteers passed around cold pupusas and carnitas that loving wives prepared back home in California. Everyone was quiet, sitting in the shared disappointment of the failed mission. I thought of the call they’d have to make the next day to the young man’s family. How would his mother react, his family, his friends? This was their last hope, and it was a failure.

I felt like a failure, too.

That evening I noticed that Rubén had been standing in the same place for a while, looking at the ground. We made eye contact and he called me over. He was standing in front of a large anthill and asked me to observe. After a few minutes in silence, he said he loved watching the ants at work—how they labored together, how each played their part, their ability to carry a heavy load.

“Ants are amazing,” he said.

I replied that I wished humans were like that too.

He said, “Just focus on your load.” Then, he left me standing there alone.

That night I lay under the kind of starry sky that one can only see in the desert. If you’ve ever been to “dark sky country,” you know what I’m talking about—it’s an incredible sight, you can see the Milky Way, and, if you’re lucky, you can even catch a comet burning in the sky.

I felt infinitely insignificant.

I knew I should rest for the long journey that awaited us the next day. But my mind was filled with the people who’d walked on this same ground where I lay, the ones who might’ve even died here. I thought of the ants, the Blue Armadillos, and our responsibility as storytellers.

There is a lot of public discussion about the ethics of journalism, and our duty to neutrality. The belief that a “good” reporter is just a spectator, detached from the work, and, therefore, the people we report about. But, for me, some things have always been crystal clear: There is legality, and there is humanity. In the middle, there are real people whose lives are at stake.

No one should have to take their last breath alone in a desert in search of a better future. So many of us have more than we need, while so many don’t have enough. I wish the Blue Armadillos, and groups like them volunteering here in the Sonoran desert, didn’t have to bear the weight of this.

But, until then, I’m glad to know they’re here.

Carrying their share of the load.

Epilogue

That Sunday, after two days and a night in the desert, we headed back towards Ajo. Ten minutes into the ride back over a bumpy dirt road, the Blue Armadillos’ van suddenly stopped. “The smell of death is unmistakable,” one of the volunteers explained as he shoved his boots back on over swollen feet.

We spread out again and searched under dry brushes, trees and ditches on the side of the road for over an hour. Then, someone pinged the radio. They thought they found a human bone-—maybe from a leg, someone hypothesized. We looked around for more remains, but had no luck.

There was some debate about whether the bone was human. One of the volunteers took a photo, they measured the bone and compared it to a chart of human anatomy, and wrote down the GPS coordinates and contacted Pima County. They left the bone back exactly where they found it and marked it off with some bright tape.

Nearly a year after this trip, I checked the Humane Borders map of human remains again. I had written down the coordinates too. There it was, identified by the medical examiner as human. No name, no gender, one more unidentified person. Hopefully, one day, these remains will find their way back to their loved ones, where they belong, and finally they’ll be buried and honored in their ancestral home the way they deserve to be.