Reporter’s Notebook

How reporting “48 hours at El Refugio” helped me to hold onto hope: a reporter’s notebook

Table of contents

For nearly two decades, investigative reporter Julieta Martinelli has covered immigration across the US and abroad. Now, while reporting at a hospitality house near Georgia’s Stewart Detention Center, she reflects on how much has, and hasn’t, changed. Confronted with familiar patterns of enforcement and fear, she holds on to the helpers and the acts of solidarity she’s witnessed along the way to stay grounded in hope.

Reporter's Notebook

It’s been nearly twenty years since my first front page byline as a newspaper reporter covering immigration in Georgia. Our recent collaboration, “48 Hours at El Refugio: A Haven for Families of ICE Detainees,” about a hospitality house near an immigration detention center in southwest Georgia, brought me all the way back — not just to reporting on my home state after a long time, but to how little seems to have changed for the better for immigrant families since.

A Growing Concern

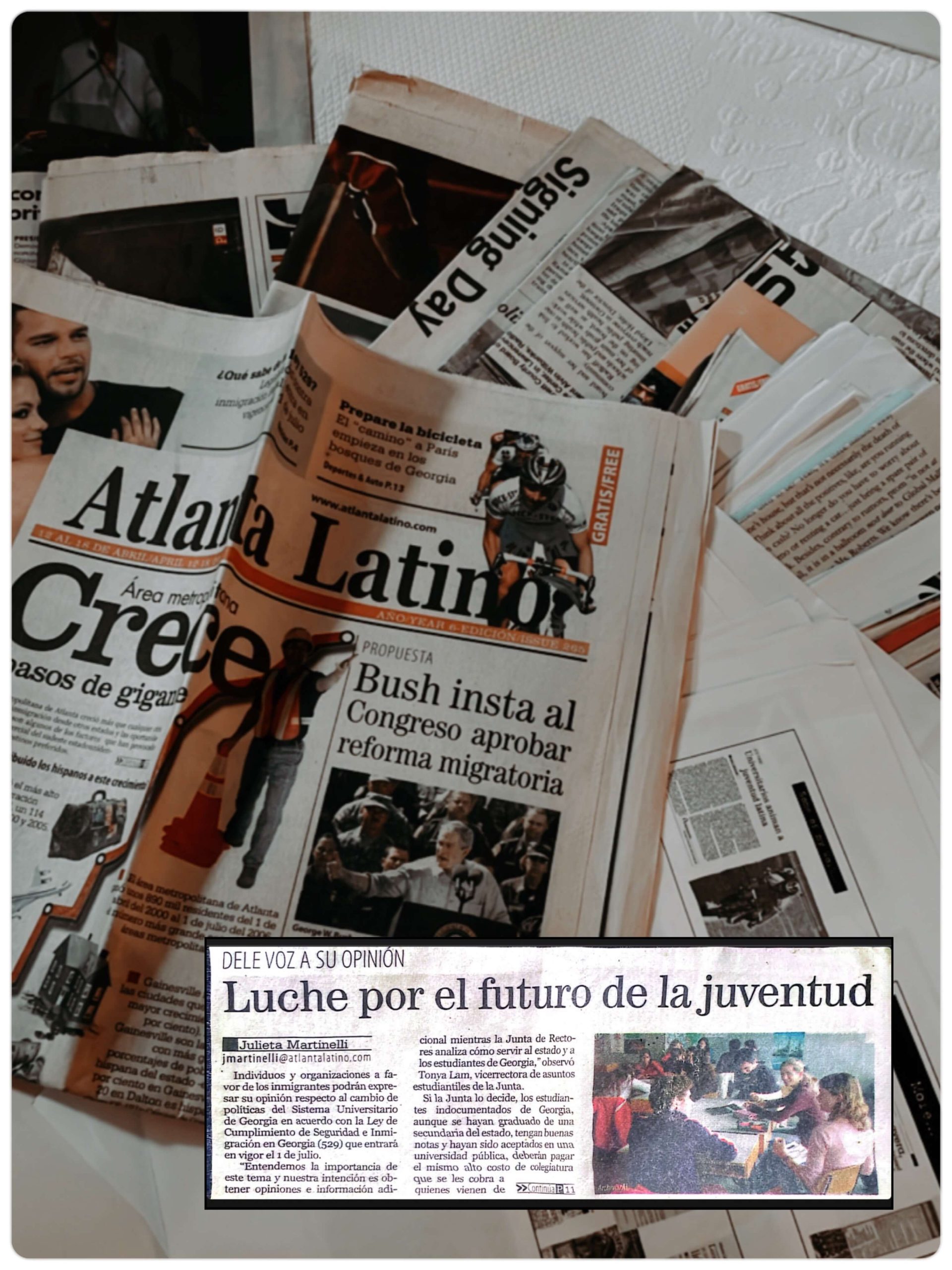

I began reporting on immigration in 2006 at Atlanta Latino, a local Spanish-language newspaper. I was eager to join a newsroom covering the issues I witnessed in my own community with greater nuance.

It was a time of growing turmoil in Georgia. My colleagues and I wrote about ICE raids, police roadblocks, and the legal maneuvering to keep undocumented students out of Georgia’s public colleges. And, eventually, the ultimate boogy-man: 287(g).

287(g) is a reference to a subsection of The Illegal Immigration Reform and Immigrant Responsibility Act of 1996. In practice, it empowers local and state police to act as de facto immigration enforcement agents, granting them the authority—under the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) direction—to perform certain federal immigration enforcement functions.

In 2007, Cobb became the first county in Georgia to implement a 287(g) partnership with ICE. Over the following two years, some of the largest counties in the state followed, including Gwinnett County, where most of us lived and worked.

As this partnership between law enforcement and federal immigration rolled out across the state, the impact on immigrant communities was almost immediate.

Coupled with federal Real ID legislation and new state policies prohibiting the issuance or renewal of licenses to drivers without legal status, we began to see police checkpoints at all hours of the day and night. Sometimes you could observe DHS buses off to the side, waiting to take people into detention for traffic violations that were now treated as crimes.

A number of longtime residents–people with jobs, homes and children–were pushed to deportation proceedings over expired licenses. We wrote about ICE showing up at apartment complexes at dawn, rounding up people on their way to work.

It was around this time that I learned that it was important to also seek out and write about the helpers. We told the stories of the Facebook groups that were created, the text chains and apps that mapped police checkpoints in real time –the improvised networks of strangers looking out for each other.

Our newspaper didn’t survive the 2009 market crash. And now, almost two decades later, I have found myself pulled back to the memories of those early days of my career over the past few months, while reporting our story on El Refugio.

The connection is not casual. Those stories from my old days hold a clue as to how it is we found ourselves here today.

A few years ago, following the election of a new sheriff, Gwinnett County finally ended its 287(g) agreement. The same county that was once a nationwide leader in ICE holds was the one to say “enough.” Cobb, the first county to join, also ended its partnership with ICE. When it finished, you could almost feel a collective breath of relief from immigrant families.

But the feeling didn’t last long. Last year, Georgia passed HB 1105 –a state law requiring sheriffs and local law enforcement to cooperate with federal immigration authorities by checking the immigration status of anyone detained in a local jail.

An Open Hospitality House and a Closed Off Detention Center

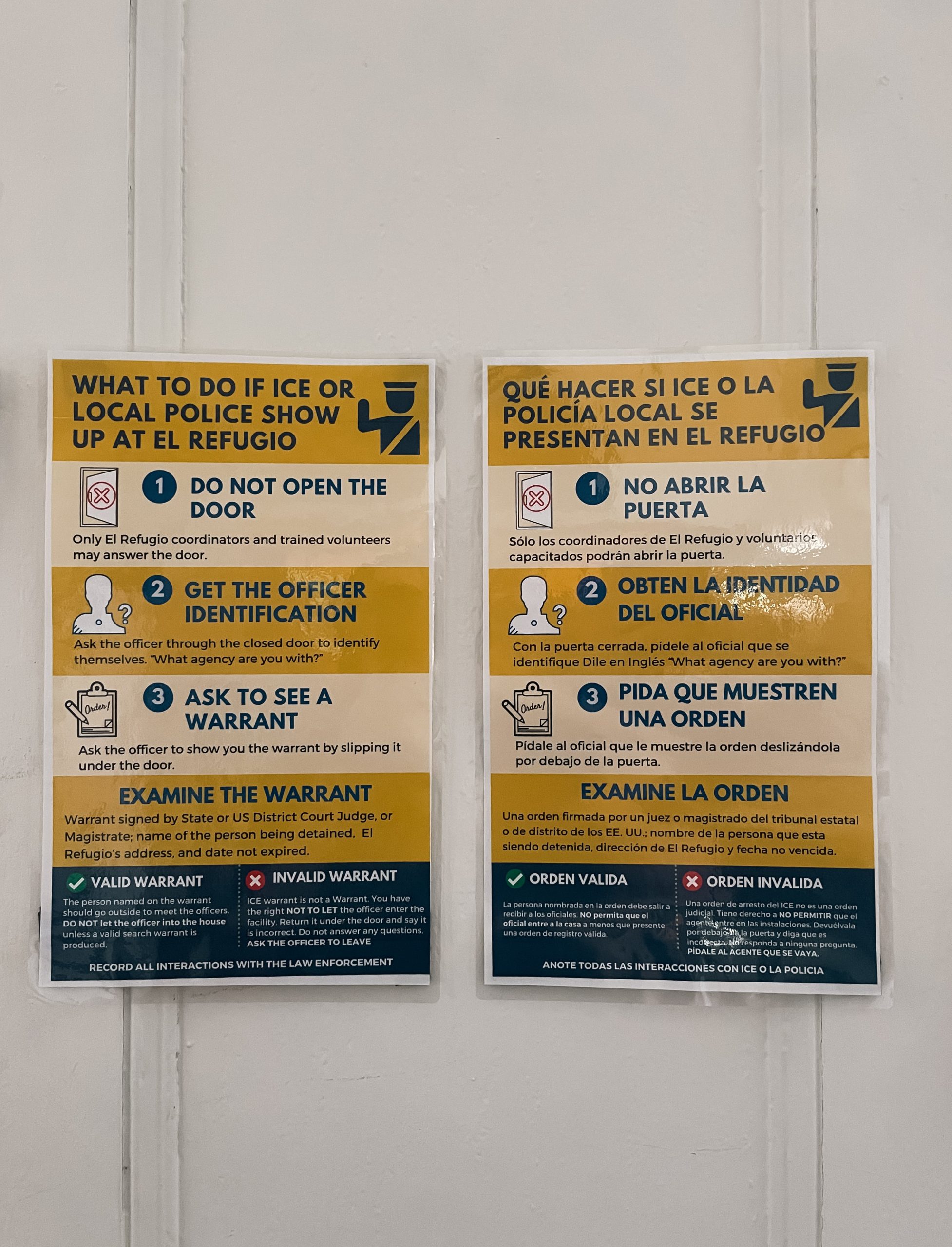

These were my thoughts as I made my way to southwest Georgia with reporter Shannon Heffernan from The Marshall Project over this past Labor Day weekend. We planned to spend the weekend at El Refugio, a one-of-a-kind hospitality house for the families and friends of people detained inside Stewart Detention Center. Stewart is one of the largest immigration detention centers in the country. It’s located in a small rural town called Lumpkin, with fewer than 1000 residents. There are no grocery stores or hotels in town. It’s so isolated in this agricultural region that the drive down and a weekend visit are challenging.

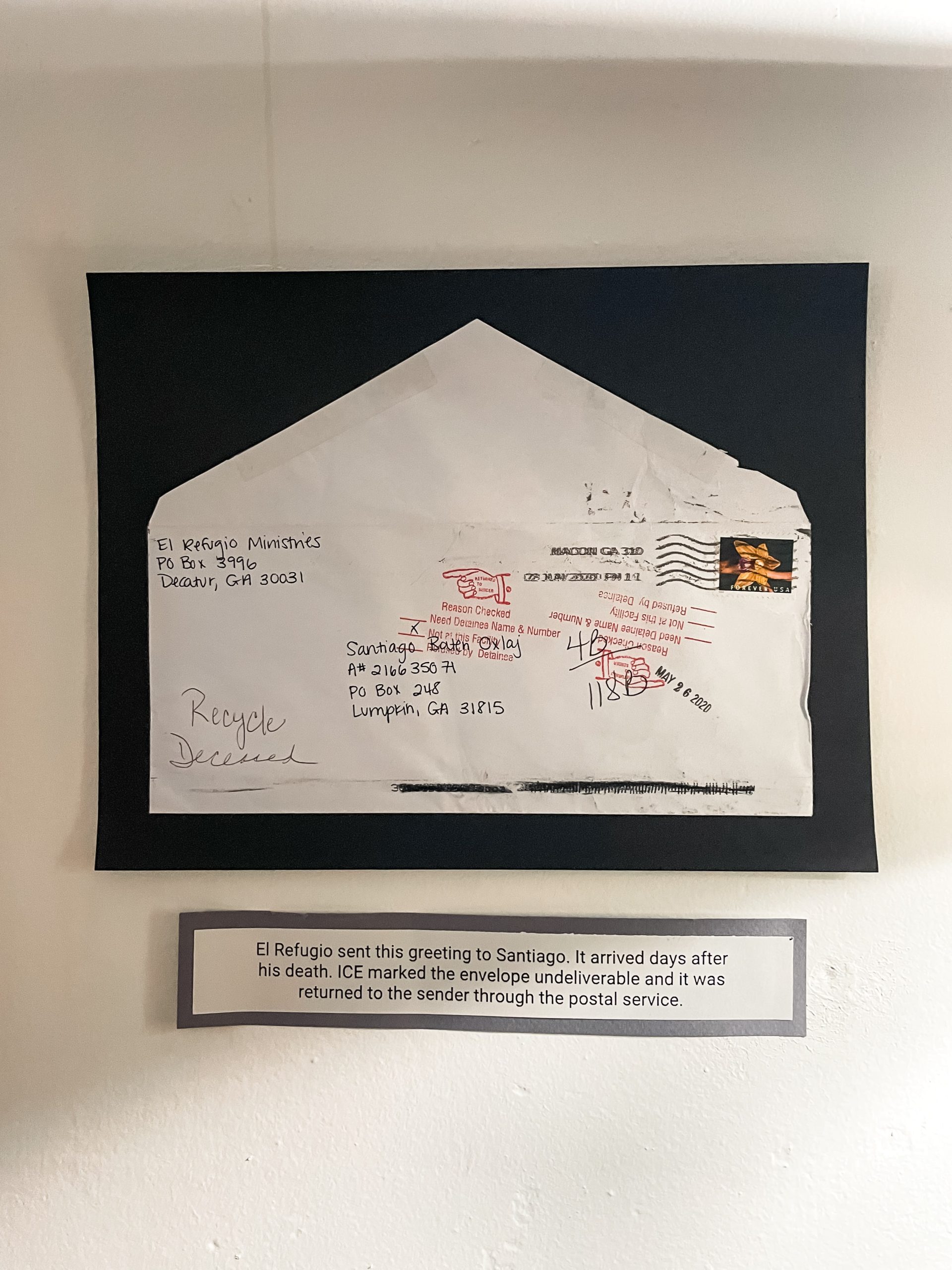

Stewart Detention Center opened in 2006, the year I began covering the chaos of immigration enforcement. By 2011, it was the biggest and busiest detention center in the nation. So many people were in custody, and so many families were passing through this sleepy town, that El Refugio was born. Volunteers would prepare beds, cook meals, and support families in town for visitations. Volunteers also began visiting people inside the detention center and learning more about conditions inside.

Fifteen years later, El Refugio still stands. And so does Stewart. This facility is no longer the biggest or busiest immigration detention center in the country. Even as it breaks its own population records, reporting over 2000 detainees at points this Summer.

That’s how much immigration enforcement has ballooned across the country, with nearly 66,000 people in custody as of last month. The largest number in U.S. history. In our podcast and print story collaboration with The Marshall Project, we break down what we witnessed at El Refugio, what families are experiencing, and how things have changed under Trump’s second term.

A New Wave of Enforcement

Earlier this year, in one of his first acts as president, Donald Trump signed an executive order directing the Department of Homeland Security to expand 287(g) partnerships. Hundreds of sheriffs across the country applied. Request petitions rose from 135 in January 2025 to 649 only six months later. According to ICE data from November 2025, Georgia now has 30 counties participating in 287(g). Across 40 states, more than 1,000 counties have current agreements with federal authorities.

The weekend I spent at El Refugio with my colleague from The Marshall Project was filled with interviews — five dozen people walked through those doors. We spoke to nearly all of them. It was a back-to-back deluge of tough-to-hear stories with similar timelines: people getting arrested, loved ones’ lives completely and suddenly changing, all happening in places so close to home. And it wasn’t just Latinos; people from all over the world were caught up in the web of immigration enforcement.

When people told stories of their family members’ arrests, I could visualize them. I know these places. I grew up here. These ordinary places, like that one gas station in a wealthy suburb outside Atlanta, where I once cleaned houses with my mom, are now the epicenter of a traumatic life change for a woman who shared the story of how her husband was taken by ICE after stopping there to pump gas.

And her story is not different from others I remember from 2006, when I was a very young reporter, thinking things couldn’t get worse. Over the years, as I moved away and began reporting national immigration stories, I came to see things like the end of 287(g) in my hometown as signs of a changing tide.

Then, I stepped into El Refugio.

Almost every family we spoke with for our reporting had been in this country for an extended time. These families had jobs, homes, children, hopes and dreams built in this nation. A number of them were even in the process of adjusting their status. They were trying to do things “the right way,” and found themselves at the mouth of the wolf.

I thought then: things could actually get worse.

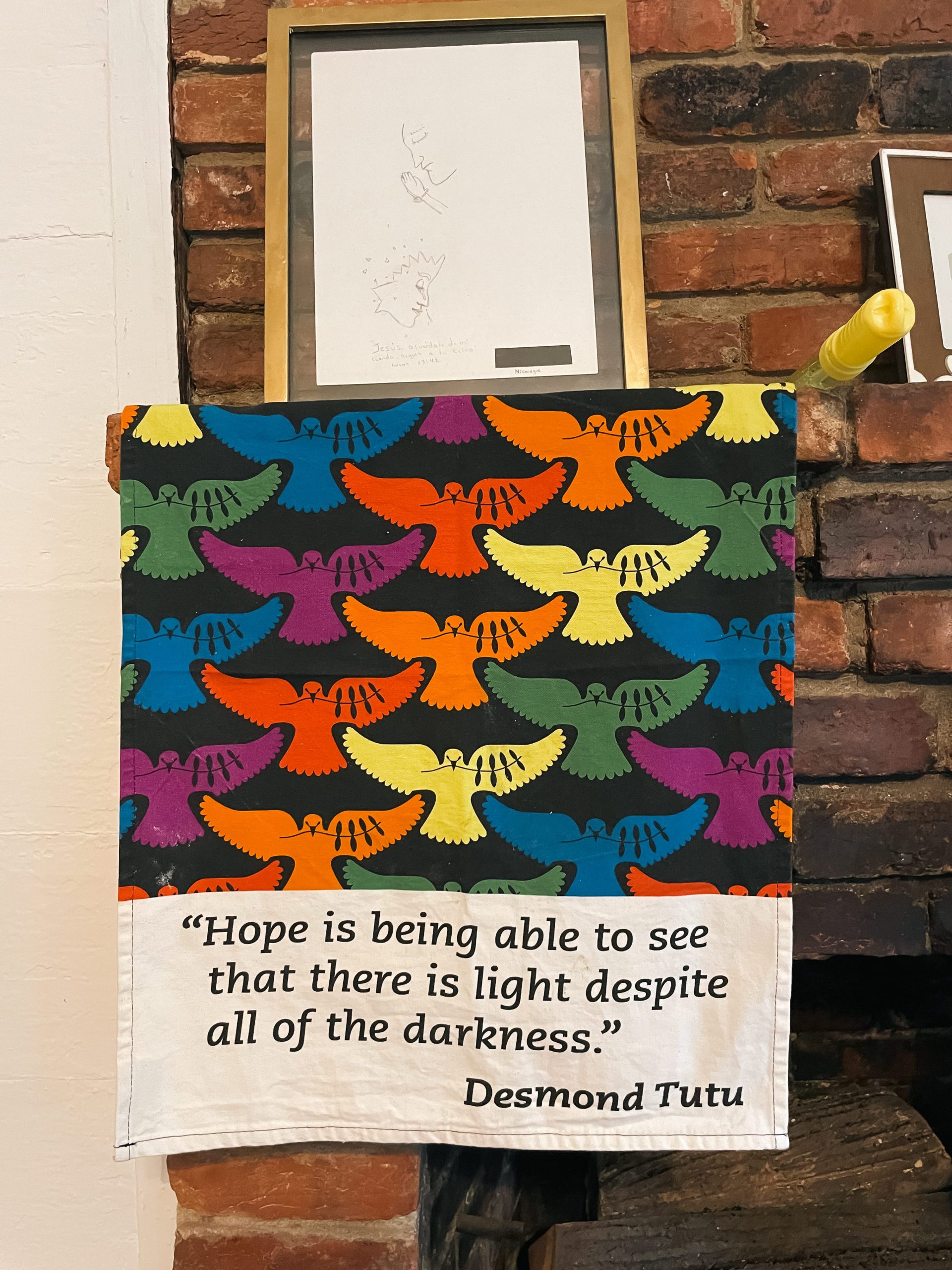

As I was scripting the radio story, I struggled to write an ending – it certainly isn’t a happy one. So, what is the conclusion? What do we take away from all this? I can’t make that call for our audience. But I can say: I have chosen to focus on hope.

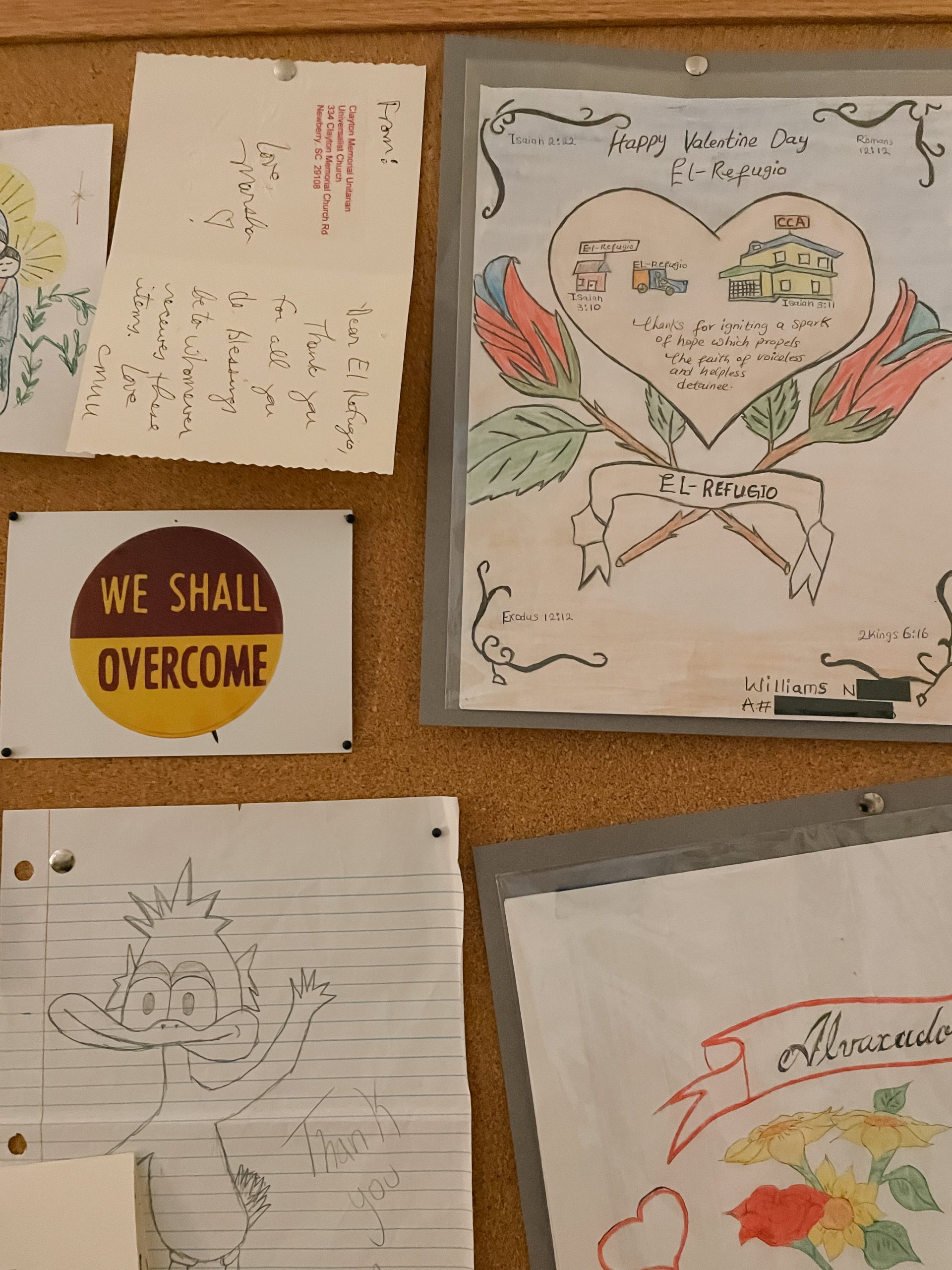

Systemic change is slow. And often it veers back and forth through the whims of time. But at every stage of my career, even in the darkest places, I have found that you can always find people trying to make things just a little better for each other. At El Refugio, I saw it in the volunteers and in the families connecting and supporting one another.

The helpers and doers have always been there. They were there twenty years ago, too – sending text messages, driving around looking for roadblocks, setting up ICE alerts. They were then visiting detainees and opening up a place like El Refugio.

As immigration enforcement continues to swoop down on unsuspecting communities, there are more helpers than ever reacting to this moment. And there is also where my work stays.